I won’t belabor the point, but if you’ve been here a while, please consider a paid subscription. It helps keep paywalls off posts like this one.

Part 1 left off with an exploration of how “our affliction is a sacred wound,” and how walking our walk in the world sometimes requires that we limp our limp.

Eventually we may even come to thank our afflictions for the teaching and transformation they bring. The lowly wounded heel, that seemingly cursed and festering thing, has the power to awaken us to who we are and what we are here to do.

Divination: Tracing the Wyrd Thread

Modern society may be skeptical towards teleology, the idea that life has any purpose at all. Even so, that ‘who’ (as in who we are) and ‘what’ (as in what we’re here to do) have long been a subject of great interest. Across cultures and continents, the world’s heritage includes countless ways of helping answer precisely these questions. Methoids include the rich tapestries of myth, rite of passage ceremonies, and the kinds of sacred games collectively known as divination.

Divination methods—‘games of the gods,’ as Nigel Pennick calls them in his book of that title—were and are intended to “provoke omens1” in order to help people become conscious of their particular threads of affinity, purpose, or karmic entanglement. These weird threads (from the Anglo-Saxon wyrd, or fate) are the themes we rub up against again and again at life’s fateful junctures as we seek to untangle the snarl and free the gifts we’ve brought with us to life.

Meade again: “Gifted and wounded, that’s how we arrive in this world…gifted and wounded, wise and crosswise, the human soul carries its complexities and seeks to unfold them” (ibid, 215).

One of divination’s primary aims is to shed light on these matters of fate and destiny. Doing so means tapping into what Meade calls the ‘otherworld’, the Chinese call tian (heaven) and Jungian psychology calls the archetypal realm. But bridging the gap between this world and that one calls for extraordinary measures, since nothing entirely of this world can reach beyond it. A quantum leap is in order, and with it a surrender to a higher order of meaning.

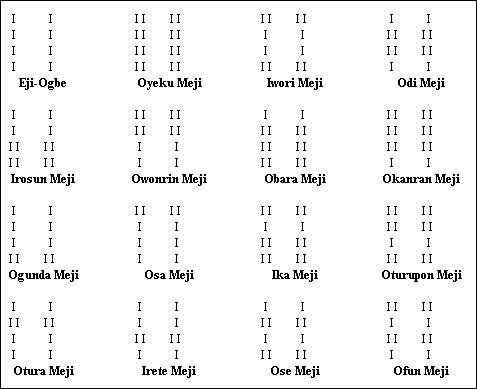

This opening to the unknown is something divination achieves through appeal to chance, the handmaid of fate. Casting bones, marking sand, counting yarrow sticks, or pounding palm nuts are all ways to generate fruitful symbols. In some cases, the symbolic images come by way of the world’s oldest binary code, a kind of proto-computer whose words are represented, in Chinese traditions, by sequences of whole and broken lines.

Perhaps you’ve seen then tattooed on a forearm, or in the dusty pages of a book.

These barcode-like figures serve as keys to vast bodies of symbols, stories, aphorisms, rituals—all in a sense ‘prescriptions’ to re-connect the querent with her original nature and innate potential. In this sense divination’s intervention is at the level of narrative: it helps people reconnect with the larger story they’re here to live, as opposed to the petty, distracting stories with which we get entangled.

Of course divination is commonly used for more mundane concerns as well as heavenly ones, and in the many gray areas in between. Here’s an example of how it can work, a true story of a mother’s encounter with the West African oracle known as Fa or Ifá.

A mother was having trouble with her teenage son. Despite her pleas, threats and cajoling, he wasn’t coming home from school to look after his little sister; he was staying out late and generally refusing to take responsibility. She in turn was punishing him by withdrawing his privileges. They were at an impasse. At her wit’s end, the woman consulted an Ifa diviner. He consulted the oracle on her behalf, pounding the palm nuts and marking the figures in iyerosun powder on his opon tray. Upon seeing the resulting odu (divination signature) told her: ‘Ifa says a prince without a kingdom is no end of trouble. Ifa says give the prince a key.’ The diviner looked at her: Ifa says to give your son a key.

A key to the house, thought the woman? That’s crazy! He and his friends will destroy the place!

But the diviner was firm and the woman, having consulted the oracle, had little recourse but to follow its advice. With much trepidation, she gave her son a key to the house. And what happened? He began coming straight home from school, taking care of his little sister, and acting like part of the family. The counterintuitive advice turned out to be the perfect remedy for the situation; in entrusting her son with responsibility it was as if she had summoned the responsible part of him into being.

One other brief example from my own divination experience, this time with the Yijing.

I once cast the oracle for my mother when she was deep in the crisis of my father’s decline due to dementia. My heart sank when I saw the hexagram that emerged for her: number 29, Kan, the image of an abyss or chasm. This is one of the darkest and most difficult of the Yi’s sixty-four hexagrams. “Great, I thought, more bad news…” Yet my mother clearly felt this was the appropriate symbol for her situation. Perhaps for the first time, its gravity, difficulty and danger were being recognized explicitly. No sugar coating would have done. Instead, the darkness had been named—and in being spelled out, it could begin to be reckoned with.

These examples hint at the kinds of healing that divination can trigger in ways that are subtle and yet potent. A day, a month, a year in one’s life can hinge on such a reading.

On the other hand, divination methods can occasion tremendous confusion if they are handled without resonant attunement, and can have disastrous results if allowed to become corrupted. Proper alignment is critical.

The Warrior’s Why-Arrow

In its reliance on random processes like coin flips, the diviner’s art can be said to work via quantum weirdness, synchronicity, or “psycho-magic” (to borrow a term from Jodorowsky, whose work I touch on here). Even before that, though, divination depends upon alignment between the mundane self and other, otherworldly part of us—the ‘higher self’ above, and the ancestors below.

In this context Yarrow emerges as a natural plant to use in divination, for Yarrow strongly represents the axis mundi or vertical pole threading the earth together with the subtle realms positioned, in esoteric cartography, above and below. This emphasis on the vertical is apparent in the form of the plant, with its straight, rigid stalk, and equally so in the herb’s name. Yarrow is Y-Arrow, like the y-axis in an algebraic graph.

Like master marksman Chiron, Yarrow helps us focus and aim unerringly at our target: in this case our destiny, our “why.” Yarrow is Why-Arrow, a guide to aligning with purpose.

But unlike axes, arrows are directional, with just one head—so which way does Yarrow’s vertical line point? I recall the Yijing’s message to me at the start of this project: Down, not up. Like the letter Y itself, Yarro'w’s gesture is to receive from above and transmit downwards. Antenna-like, Yarrow helps us ground the signals from the subtle realm. It directs our feet to help us walk our walk (and limp our limp) here on earth while staying connected to higher purpose and inner truth.

‘Higher purpose and inner truth’ may sound well and good, but living in accordance with them means coming into conflict, sooner or later, with the less noble elements of our mixed-up world. In an off-kilter society, to align along the (wh)y-axis is to take a radical stance. One who commits to such alignment and to limping the soulful limp of the healer must also develop the virtues of the warrior: courage, first and foremost, to stand up for what is right. The archetypes of healer and warrior turn out to be inextricable.

Yarrow helps us embody them both as we dance, limp, and stumble our way through our stories. Yarrow teaches us to honor or wounds and to heal them; to walk our walk, limping if necessary, as we learn to dance.

Yarrow, Boundaries and the Bladder

Stumbling feet, wounded feet, dancing feet; if Yarrow is the healer’s herb, then it is also the herb of heeling, as in reining in, stopping. The healer must learn to heel, to say ‘no’ to the forces of disease. Yarrow is used to strengthen boundaries. The plant itself likes to grows around edges and perimeters, and that’s where it gravitates in the body: to what Chinese medicine calls the taiyang (great yang), our outermost physiological layer. The taiyang boundary constitutes both the epidermis and the mucosal lining of our digestive tracts. Yarrow helps to tighten both, in effect helping us say ‘no’ to would-be infiltrators in the form of ill wind, pathogens, or allergenic food proteins. For this reason it is useful for all kinds of hypersensitivity, both allergic and emotional, as it effectively erects a screen to fortify our defenses and deflect the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”—except where fate would decree we be pierced.

Yarrow’s affinity for the peripheral dovetails with the archetype of the wounded healer in another way: as Philoctetes’ story demonstrates, the wounded warrior/healer is often a liminal character, occupying borderlands; ironically, given her ability to serve as a central conduit, the medicine man or woman is classically found on the outskirts of town.

Fittingly, the acupuncture point nearest the Achilles heel lies on the Bladder channel, the Bladder being (along with the Small Intestine) a taiyang organ. In the body politics of the Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic (Huang Di Nei Jing), the Bladder is described as the official of the border regions—necessarily, then, a kind of warrior, prepared to defend the interior from outside invaders. Not only is the acupuncture point in question associated with this border official of an organ system, but the point itself is called Kunlun, a reference to a mythical mountain that serves as an axis mundi or vertical axis. Like Yarrow, the point Kunlun, Bladder 60, has to do with vertical alignment, vulnerability and the spiritual warrior. One might apply Yarrow oil to Bladder 60 to mark a commitment to the sacred path shared by warrior and healer alike.

Yarrow’s connection to the Bladder organ system is also borne out by Yarrow’s efficacy in treating a host of urinary issues from UTI’s to incontinence.

Yarrow’s namesake resonance with Achilles is supported not only by its connection to the heel, but by its capacity to staunch severe bleeding (it’s for “cuts to the bone”, according to herbalist Matthew Wood).

Connecting Heaven and Earth

If part of our tragicomic human predicament is to be caught between these two realms, with one foot in eternity and the other right here in the mud, then it is our burden and privilege to serve as conduits between them. Yarrow stands here with us in vertical alignment. Serving as sentry, it guards the threshold to the path of the healer and warrior: pierced by time, wounded by fate, dripping our heart’s blood onto the witnessing earth.

Veteran Yarrow reminds us of the necessity of our wounds, without which our inner light could not leak out for the world’s benefit. Our wounds are sacred portals that needed to be opened—but that also, as at least one version of Philoctetes’ story tells us, may be healed. “Pursuing one’s destiny depends upon…healing one’s inner wounds,” Meade writes. He reminds us, too, that “once healed over, the wounded places often become stronger than normal tissue. Healing makes a person stronger than before the wounds were faced and treated” (ibid, 217). Healing, we gain the courage to fight our battles—and to help others heal.

Sources

Fruehauf, Heiner. Lecture notes and personal communication

Liu, Ming. Changing: Zhouyi: The Heart of the Yijing

Meade, Michael. Fate and Destiny: The Two Agreements of the Soul

Meade, Michael. Men and the Water of Life

Pennick, Nigel. Games of the Gods

Sophocles, tr. Moses Hadas. Philoctetes.

Wilson, E. The Wound and the Bow

Wood, Matthew. The Book of Herbal Wisdom

Robert Moss’s memorable phrase lends its name to this section of Seeds from the World Tree.