1.

We start firmly in the realm of the mundane, with a colleague who posted the other day on social media to ask whether it was normal to receive a rejection from an institute or foundation without a word of explanation. Perhaps he was just being old-fashioned, he said, but it seemed to him people used to take the time to include a polite note with these kinds of decisions.

In the way of these things, the post set off a flurry of comments. The thread became a kind of catalogue of the ways the social fabric is unraveling.

Exhibit A: the devolvement of parenting into parents asking kids “what do you want?” over and over again.

Exhibit B: Disappearance of town centers such that people no longer leave their houses or know their neighbors.

Exhibit C: Declining mental health among kids and teens.

And so on.

I’m sympathetic enough to these complaints, growing as I am (whisker by whisker) into the ranks of the grey-bearded. A certain curmudgeonliness is not amiss, nor has it ever been especially difficult to convince me that the world is sliding into the beast’s maw. The trend is not good and seems to be getting worse—who would argue with that?

But then I thought—true, but things have always been getting worse. Didn’t the ancients complain about the same things we do? Corrupt politicians, decline in societal ethics, loss of the traditions that give dignity and order to life?

Some of the earliest Chinese medical texts decry the loose habits of the (then) contemporary populace, blaming them for the rise in disease—and this was two millennia less moral decay than we’ve now had time in which to indulge.

Somehow, I thought, both things are true. We hurdle (ever faster, seemingly) toward the edge of the abyss. And we never fully plunge into screaming nothingness. The world refuses to end. Even as it’s always in the process of ending.

Of course, it’s possible that this perception of things falling apart is plain wrong. Or that the idea that the world doesn’t end is wrong. After all, the world has already ended for many species, many cultures, many languages.

But let’s say for argument’s sake that neither thesis is wrong. In that case we have a contradiction on our hands. Two observables that don’t square with one another.

Is this seeming contradiction a puzzle? If we call it a puzzle, we’re saying it’s something to be solved; we’re looking for some trick, perhaps, that will make the seemingly irreconcilable facts suddenly click into focus and play nice together.

Or is the seeming contradiction a paradox?

Unlike a puzzle, a paradox isn’t something you can solve. Although it bends the brain to do so, a paradox is something to be contemplated. Appreciated. Savored, even.

And perhaps also something to be stepped through, like a door.

2.

Paradox can be maddening from the perspective of our everyday, linear-thinking minds, the part that of us only wants to navigate from point A to point B.

The mundane mind operates on the real number line, R: that long, straight stretch of highway passing through zero and out as far as you can see in either direction, ad infinitum. All the familiar grade-school numbers exist along it: the integers, the decimals, everybody.

Which isn’t to say the real numbers are entirely devoid of weirdness. You can stumble upon plenty of creatures such as:

(“the square root of two,” in case you’ve blotted out your middle school math memories altogether). This is a real number, but an irrational one: it can’t be represented as a fraction of two whole numbers. Written as a decimal, its digits continue forever, always changing.

Irrational numbers are odd creatures, but what our everyday minds are truly unprepared for are the wilds that exist a mere step to the side of the real number line. Deviate a hair’s breadth from the straight and narrow confines of R, and you enter a kind of twilight zone where the imaginary numbers romp and roam.

“Imaginary” refers, in this context, to numbers involving i. i is defined as the square root of minus 1—an impossibility, since when you square something, the result is always positive. There’s no such number as i—not on the real number line, anyway. But suppose there were. Imagine if. Define the undefinable. Cozy up to paradox.

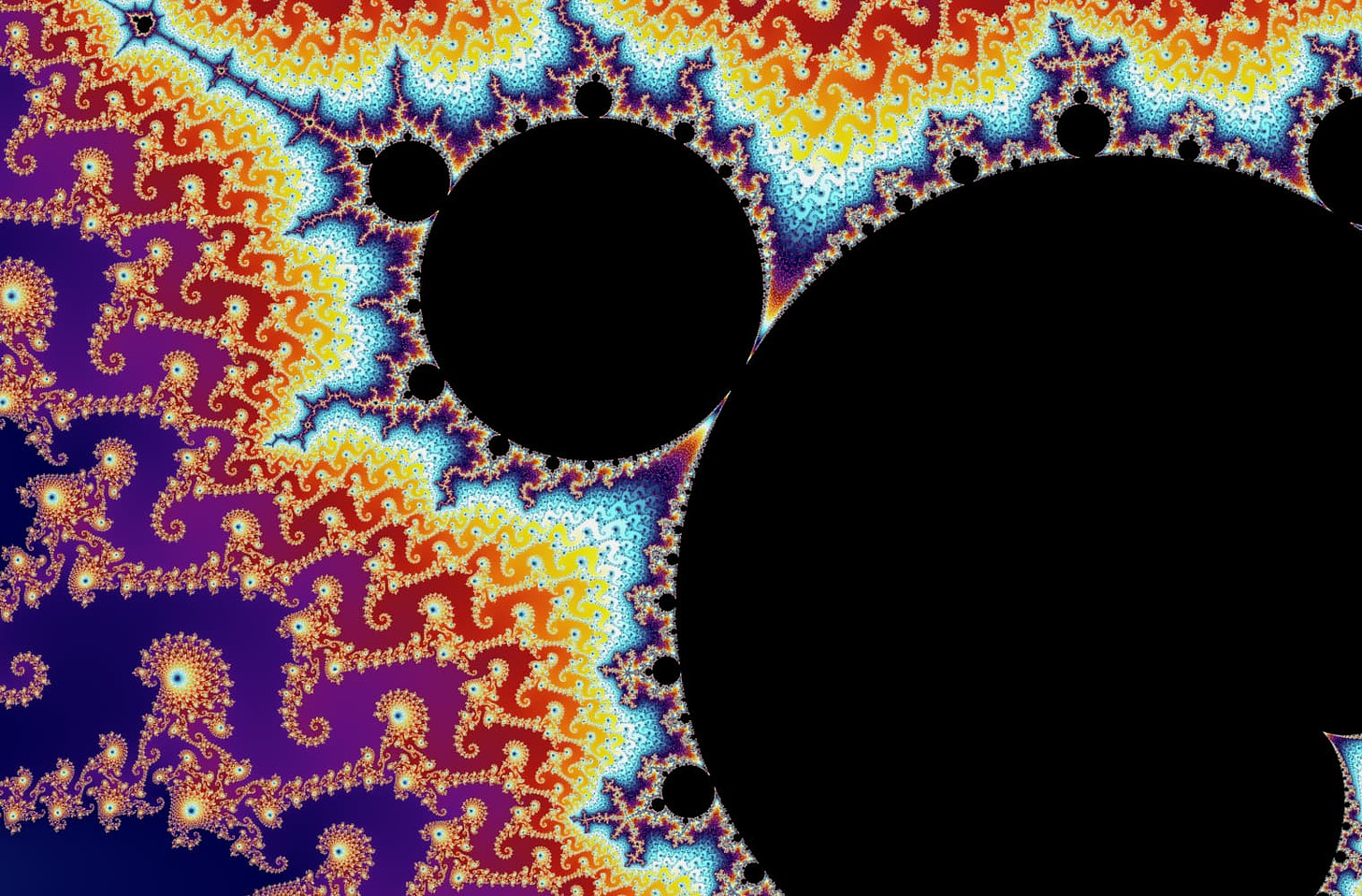

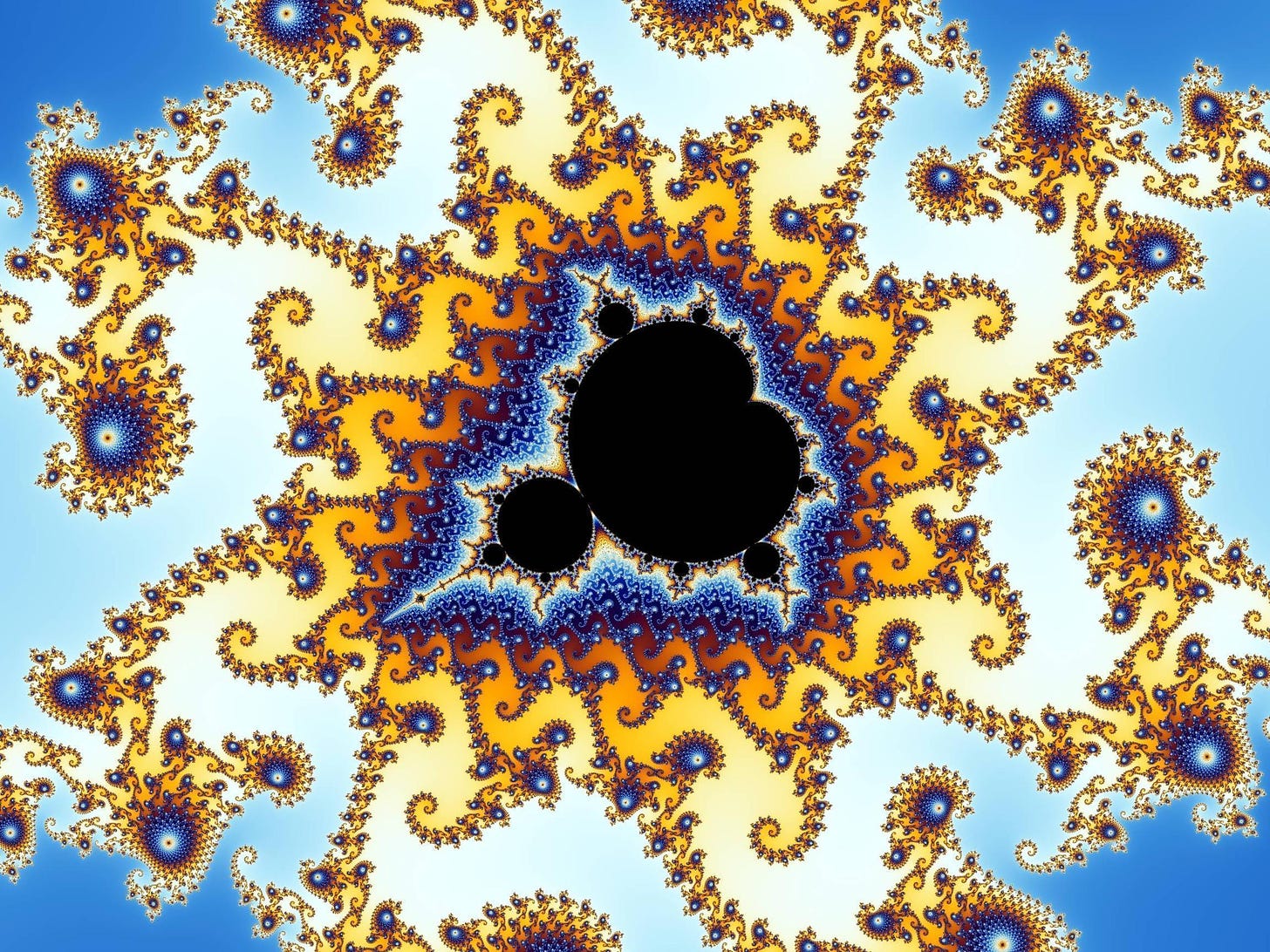

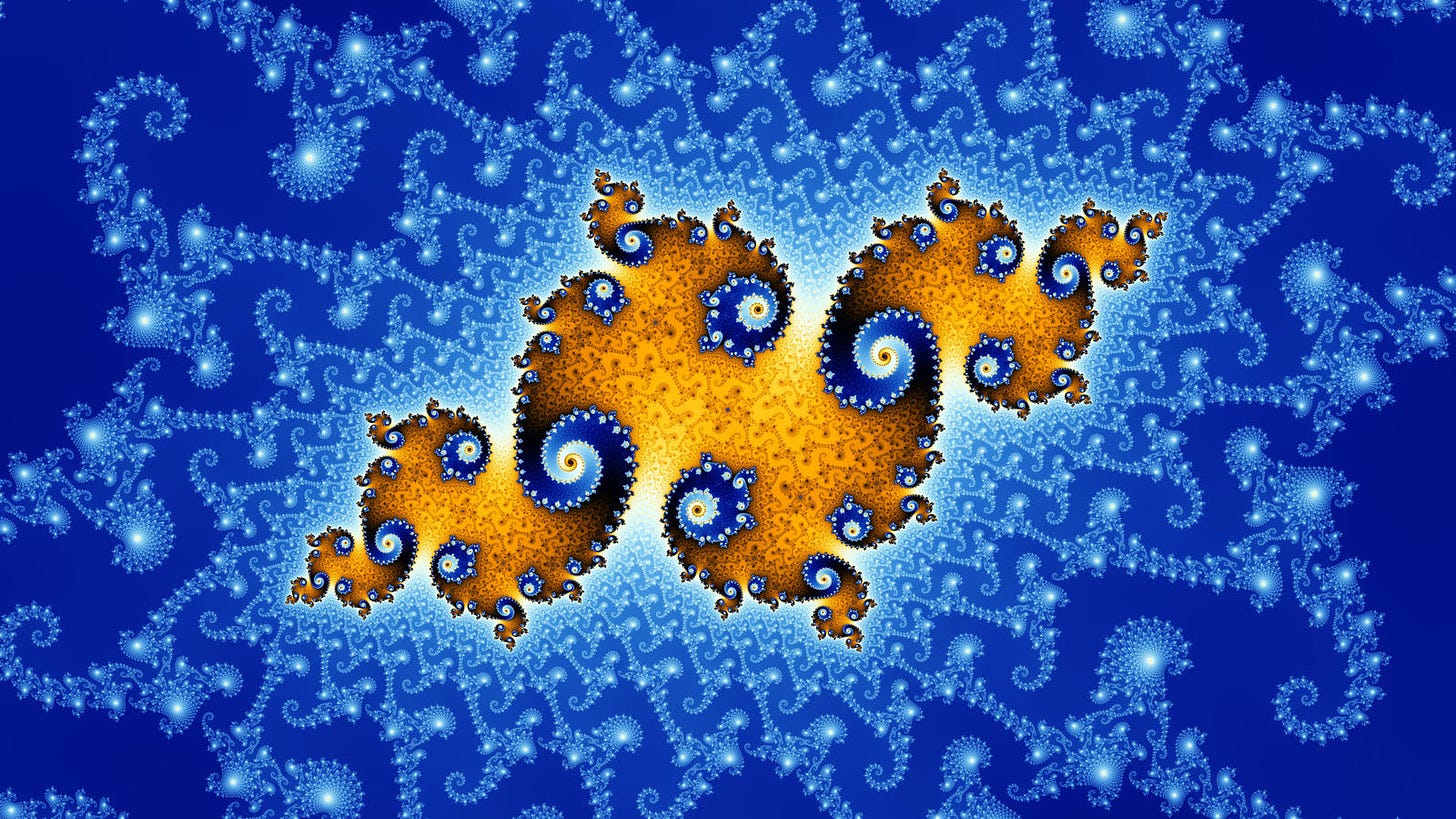

And enter….this.

This extraordinary fractal universe is perfectly real: we’re looking at a representation of it. But its underpinnings are purely imaginary, being based on numbers that don’t “exist” in the way our minds expect numbers to exist. You simply can’t count 10i or 12i jelly beans—don’t bother trying unless you’re hungry for an imaginary dessert. The idea fundamentally doesn’t make any sense. And yet it opens up a world of wonders: in this case, the stunning, intricate landscape of the Mandelbrot set.

At the risk of dredging up a term and trend that seems squarely lodged in the 90’s (along with Magic Eye-type stereographic images—remember them?), “fractal” refers to forms are infinitely intricate, and self-similar across scales of dimension. In other words, as you zoom in, there’s always more to discover, with never an end to the complexity. And yet, as you go deeper and deeper in, you’ll always arrive at patterns similar of ones you’ve seen before. The parts contains something similar, anyway, to the whole.

What we have here is an endless banquet of complexity, all from a single equation and some computing power. Without the paradox of the square root of a number that can’t have a square root, you can’t arrive there.

3.

At the altar these Navaratri nights, I invoke Sri Lalita Tripura Sundari, the beautiful and playful goddess. Lalita: she whose plays, she whose play we are.

Perhaps you’ve seen her diagram, the Sri Cakra:

She is worshipped in the form of this diagram, or as an impossibly beautiful woman, or as a series of syllables. All one.

These are a few of her thousand names1:

Sri Mata - the divine mother

Jagarini - she who is the waking state.

Svapanti - she who is the dream state.

Supta - she who is the deep sleep state

Turiya - she who transcends all states

Varada - she who bestow boons

Vama nayana - she whose eyes are full of grace

Kalāvati - she who is the embodiment of all arts

Varuni mada vihvalā - she who is intoxicated on the wine of bliss

Vidyāvidya svarupinī - she who is both knowledge and ignorance

Cetanā rupa - she who is consciousness itself

Sampradāyesvari - she who is the ruler of sacred traditions

Nirdvaita varjitā - she who has no opposite

Bali priyā - she who loves the offerings of devotees

Sarva mohinī - she who casts her spell on all

Muni mānasa hamsikā - the swan who swims in the lake of the minds of saints

Bhava dāya sudhā vrsti - she whose rain of nectar puts out the wildfire of samsara

Śāntyatīta kal’ātmikā - sho who transcends even the state of peace

Gambhirā - inscrutable

Seated at the altar, I recite what little of her name-garland I have committed to memory - a scant few Sanskrit couplets. As a kind of shorthand, I chant a simple song stitched from the first and last of those names. Sri Mātā, Lalitāmbikā. Over and over, alpha and omega, stitching end to beginning to end, doing my best to stretch my mind around what lies between.

I picture Her in her refulgence, she “in whose rosy splendor the whole universe is bathed.” Eyes like fishes swimming in her waxing-moon face. Delighted laughter a cascade of falling stars.

I imagine the ineffable vastness of the cosmos: that vast is she. The cyclical beginning and ending of the universe is but the fluttering open and shut of her eyelids.

I bring my attention back to myself: a tiny molecule within that vast ocean of existence. Yet she is within me. Reminds me that I, too, contain vastness. The drop contains the whole, while the whole contains the drop.

Paradox.

I do my best to let the contradictory notions coexist in my awareness, humming and beating against each other like two musical notes out of phase.

I stay with that tension, and out of it arises something different. A third thing is born of the two; a doorway appears as if from a pop-up book page. She is there. Here. I catch her smile, see her beckon.

And step through.

4.

Imagine a child blessed and cursed with different color eyes. Not just eyes of different color, but radically different kinds of eyes.

On one side—the left, say—the eye is silver-grey. Its gaze is sharp, clear, dry and precise. This eye, an eagle eye, sees in high resolution. It can lock onto a detail and zoom in 1,000 times. In just the right light, at the right angle, you can catch a glimpse of the circuitry behind this eye, this machine eye. Gears, lasers, flashing digits at work. To look at this eye is tingle or tremble with the knowledge of its power, to chop the world into a million tiny pieces. To look through it is to wield that power.

The other eye is—what to say about the other eye? It lacks the precision of its mate. It’s blurry, unruly. Yet undeniably beautiful. Dancing symbols seem to flow through the iris (a word which, let us recall, means “rainbow”) in a technicolor cloud. This eye brims with tears; it glints and gleams with violet and gold. It fluctuates, undulates, traces an ouroboros on itself. To look at this eye is to be enchanted, in love. To see through it is to see an enchanted world, a world of wonders.

Should we pity the child born with such a pair of eyes? Oh, the headaches she will have, trying to see through both at once. Can we blame her if she squints, covers half her face, resorts to an eyepatch? No doubt she has terrible days, gazing at one eye with the other. At times she feels herself torn in two—or is it the world that’s torn?

Covering up is painful, but simple. Even if the world is diminished, at least she can move without the dreadful dissonance of being at war with herself.

Some days, she covers the right. All resolves into clean lines, shades of grey, silent statistics. Never an error to be found in the data. There is no feeling, no warmth here; no color and no confusion.

When she can stand it no longer, she closes both, tries to sleep.

The next day, she shifts the eyepatch to the left, coaxes the gummed lid of the right open again.

All at once the world swims with beauty, and an echo of horror; all colors are here, and meaning oozes out of every form. It is delicious, delirious, nauseous. Nothing will sit still. There’s no resolution to be found, only gyration and clouds of velvet butterflies.

Enough. She squeezes shut again, exhausted.

When she’s ready—when the pain of shutting the world off outweighs the pain of opening back up—she’ll try again.

Selected names of Sri Lalitā are from the Śri Lalitā Sahasranāma (1,000 Names of Sri Lalita) translated by Swami Tapasyānanda, published by Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, India. For a chanted audio version, try this one on Youtube.