It’s a truism that less can be more, even a cliché. But for the Western mind—by which I mean roughly those of us raised on sugary cereal and cartoons for breakfast—the truth of the phrase is not easy to internalize.

When, exactly, is less more?

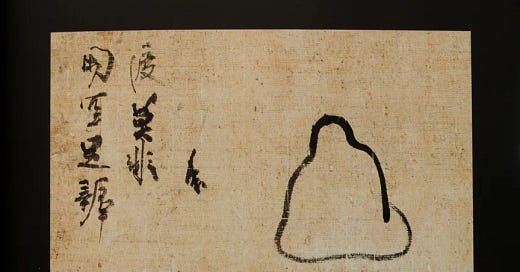

Japanese aesthetics come to mind: the clean lines, the minimalism we sometimes associate with that country. You don’t want to clutter up a haiku; or rather, as soon as you add clutter, the haiku ceases to exist. An art of omission, the form depends on empty space.

Music can be like this, with silence as important as any sounded note. Bebop isn’t the most minimalist of musics as a rule, but Miles Davis’ sly horn knows just where to cut out, and that’s what gives his sound its undeniable authority.

Then in cooking, there’s no improving upon certain elemental combinations of ingredients—bread and butter, or prosciutto and melon—provided quality is there to start. (If not, Do Not Pass Go).

We can probably agree that less is more applies in the realm of aesthetics. But what about in the practical world? Let’s consider (surprise, surprise) the realm of medicine and healing.

Here, too, it’s obvious that it’s possible to do too much. Safe herbs and drugs become toxic in the wrong dose (heck, so does water). Too many spinal fusions (maybe just one) can ruin someone’s back. Too many x-rays increase cancer risk. And so on.

What’s less is obvious is just how little is sometimes enough. It’s a lesson acupuncturists like myself are confronted with sooner or later in our clinical development—sooner, if we’re paying attention.

After only two or three needles, a patient may slip deep into beatitude, which is my shorthand for the tranced-out, angel-faced state a good treatment can occasion. Empirically, we might find that their neck tension has softened, the knot in their belly eased, their pain vanished. Then—we’re on a roll, after all—we practitioners may be tempted to do more. The patient didn’t come for just two needles, we might think. It’s only been 15 minutes. Commence phase two!

Sometimes doing more at such a point can work out okay. But just as often—and I fell into this trap not long ago—it can backfire. I had a patient go from beatific (I wish I could convey the glow) to skin-crawling-aggravated shortly after a second set of needles went in; by the time I returned to check on him, he had pulled them all himself, sometimes I’ve only encountered had one or two patients do in my decade of doing this work. (He felt fine as soon as the needles were out so this wasn’t an especially off-the-rails example—but those can definitely happen.)

Perhaps the most counterintuitive thing about the risk of over-treatment is sussing out who is most prone to it. As you may have surmised by now (if you haven’t experienced this yourself) it’s the most sensitive, delicate and weak patients—exactly those who would seem to need the most intensive help—who tolerate the least. For these patients, less truly is more.1

In the most dramatically weakened cases, a single needle or sesame-sized bit of moxa may be plenty, as illustrated in the research of Moxafrica. Working with HIV and TB patients too debilitated to get out of bed, Moxafraica researchers in Uganda found that a single cone of moxa once per day was enough to make meaningful improvements in these patients’ energy levels (subjective) and serological and immunological markers (objective)2. From the practitioner’s point of view, the road to mastery with these folks has a lot to do with learning when to stop. When to say “good enough for today.” It’s about building a fire twig by twig, holding in reserve the heavy log that would smother the flame.

The flip side, of course, is that robust patients can tolerate and often require heavier stimulation: larger-gauge needles, more of them, stronger herbs and higher doses. The average corn-and-beef-fed American may be right to want more—up to a point.

According to the Moxafrica study:

The principle positive findings were:

1. Moxa patients converted to sputum negative faster when using moxa, particularly in the early stages of therapy.

2. Moxa patients adhered to their drug therapy better.

3. Moxa patients had increased levels of Hb

4. Moxa patients had greater increases of Cd4 cells, although this data was not statistically significant.

5. There were no adverse events.

6. All of the first four findings were also seen in the HIV sub-group.