Practical Divination

A learnable mini-method for tuning into guidance and intuition

For two decades I’ve been studying and practicing divination, which we can define, per Robert Moss, as “the art of provoking an omen.”

In that time, I’ve rarely met a divination style that doesn’t fascinate and that hasn’t informed my path in some capacity.

Astrology. The Yijing (I Ching). Bonecasting. I feel mantic arts constitute an under-appreciated aspect of our human heritage. And my (admittedly nerdy) heart delights in learning the complexities of these systems and dozens of other laid down by our human ancestors to help us access wisdom.

As living, intergenerational, functional pieces of art, the big, magnum opus-level divination systems of the world have the range of expression to speak meaningfully to most any situation.

Take the Yoruba oracle known as Ifā: its diviner-priests spend years memorizing thousands of verses, so that when the oracle’s patterns land, the babalawo (diviner) can interpret without missing a beat in a manner that’s part poetry, part song, part psychotherapy.

Like the oracle at Delphi, whom one didn’t consult simply to ask after the whereabouts of a lost fanny pack, the heavy-duty oracles are well-suited for addressing major life situations.

But what about the minor and mid-grade stuff, the pocket dilemmas of our quotidian existence? These, too, require attention, and it may as well come from an oracle that’s the right size. For if complexity is beautiful, simplicity is divine.

Sometimes you just need a ‘yes’ or no,’ black or white, rather than 600 shades of crayon.

The Yoruba know this as well as anyone. Alongside the intricacy of Ifā, Yoruba culture also makes liberal use of a much simpler method known as obi, kola nut divination. In this straightforward technique, a four-lobed kola (obi abata) is divided and cast to obtain a simple yes/no, depending on which pieces fall face up or face down.

This kola nut technique is used to communicate with the deities, most typically to ask whether a given offering has been accepted. By extension, it can also be used to ask other yes/no questions, provided they fall somehow under the purview of the deity in question.

Kola divination is a language that the Yoruba deities speak, using materials grown locally. As such, it makes perfect sense within its home context1. It can be stretched, but only so far; I wouldn’t recommend trying to dial up Buddha or Jesus with a kola nut. That’s because obi divination is specific not just to a geographic area and a culture, but to a religious sensibility. That’s its strength and its limitation.

The other day I got to thinking: what about a pragmatic, accessible but less-religion-specific way of divining that doesn’t require initiation to a priesthood or intensely specialized nerding to learn?

Because, after all, most of us stand to benefit from a little divinatory know-how, no matter how disreputable the practice may remain by over-culture standards.

What we’re looking for is a system of divination that’s universal, systematic and not too complex. It should be able to yield yes/no answers while also providing some coloration and nuance. It should also be easily portable and learnable.

All told, we’re looking for a workhorse method for daily life as well as one that can serve in ritual contexts (where divination becomes especially vital).

As an aside, we should note that a totally strict yes/no method would be too rigid. What if the question posed contains erroneous assumptions? The oracle would be constrained to give a misleading answer.2 So we need some wiggle room built in.

What kind of divination styles might we consider for our workhorse?

horary astrology, i.e. casting a chart for a question the moment it is asked. This method is incisive and broadly applicable, without being tied too closely to any particular religious tradition. The problem is that it requires specialized training and either a computer or the aptitude to track where the planets are at any given moment. Verdict: not accessible enough to fit the bill here.

cartomancy of various forms (including Tarot). Depending on the card deck consulted, plenty of answers are possible, but most of them don’t provide a simple, clear ‘yes/no.’ There are some decks (such as the LeNormand) that lend themselves to practical divination better than Tarot tends to, in my experience. Still, how often do you happen to have your deck on you? Verdict: promising, but perhaps not as practical as we’d like.

a random image generator, my favorite free, open-source digital oracle. Simply go to a random image generating website like this one and you’re one click away from whatever image spirit would like to conjure in regards to the question at hand. Random images are a favorite here at Heartward Sanctuary when a quick read is required. But they do require internet access, or at least a cellular signal and a charged phone. And the answers, while frequently insightful and often hilarious (not to mention profane), are not always clear-cut. In any case, there are situations where something a little more analog is called for. Verdict: requires tech and lacks gravitas.

The I Ching. Originating in ancient China, this oracle’s set of hexagrams has long since traversed the globe and become essentially open-source. All that’s needed to consult the I is a coin or three, and a book (or phone) to look up the resulting hexagram symbols. Unfortunately, the hexagrams are so encrusted with centuries’ worth of commentary that it’s easy to get lost in the thicket of all that’s been said about each symbol. Verdict: due to the danger of ‘death by a thousand interpretations,’ the I Ching is apt to fail the pragmatism test—unless one is rooted in a specific lineage of practice that can clear up the confusion. And that’s rare.

Today I’d like to propose another option, one with ancient roots and a modern twist.

This is a method based on the eight trigrams (ba gua) at the core of the I Ching, but that avoids the myriad complexities of the hexagrams proper. A kind of mini-I Ching, if you will.

I reckon that eight possibilities is about right in terms of complexity: it’s not that hard to memorize eight patterns, nor is it hard to generate them. To do so, we’ll be flipping three distinct coins at the same time, having determined in advance which coin correspond to the bottom, middle and upper lines of the trigram.

More on the technical details in a minute.

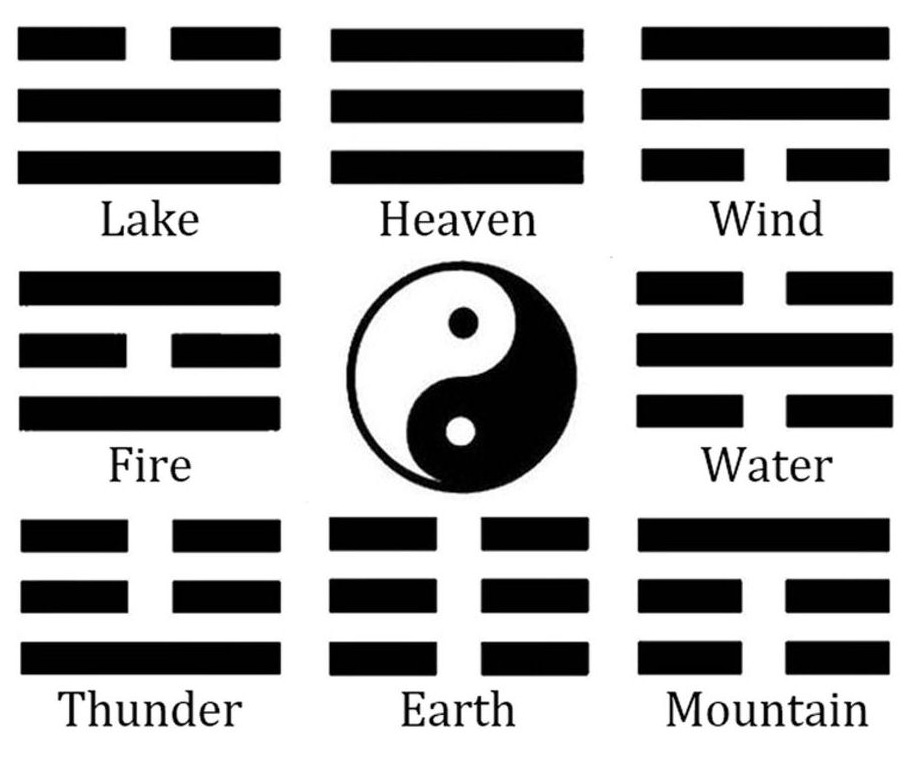

First, let’s get (re)acquainted with our main characters, the trigrams themselves. These are no more or less than 3-bit digital barcodes, with each bit represented by a yang (whole) line or yin (broken) line.

There are 2 x 2 x 2 = 8 possible combinations. Each of them has been named in association with a natural phenomenon.

There are many ways of working with the trigrams in divination. For instance, if the question is “where did I leave my sweater” we might cast a trigram and pay attention to the compass direction associated it. Or we might see (for instance) Lake (dui) and recall that we left the sweater at the pond or swimming pool (clearly it was not needed).

But for practical purposes we need a way to obtain ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ This is not something the trigrams are always called on to provide. But can they oblige?

They can.

Here’s how.

Of the 8 trigrams, two be read as a ‘yes,’ two as a ‘no,’ while the other four are a bit more nuanced or ambiguous. These ‘shades of grey’ can shed light on subtle aspects of the situation or prompt us to reevaluate the question; they can also be taken as a ‘cast again’ prompt when in doubt, as we’ll see.

Let’s look at the more clear-cut trigrams first. They are four:

Qian, heaven. three yang lines. This is our gold-standard ‘yes’ answer. Qian means spirit is moving, creativity is catalyzed, roads are open. All is in alignment to proceed.

Kun, earth. three yin lines. This we take as a definitive ‘no.’ Kun suggests inertia, passivity, rest; not a time for action. “Nothing doing.”

Li, fire. one yin line between two yang lines. This is another yes, with valences of harmony, joy, excitement, connection. However, there is a slight hint of a shadow as seen in the central yin line hidden in the center of the gua. When summer and fire are at their peak, already yin forces are creeping back in. Thus an admonition to proceed with care and proper protocol.

Kan, water. one yang line between two yin lines. With its meanings of a chasm, danger, contraction and cold, this is virtually always a ‘no.’ However, those prepared for great risk can be advised that is something of value may be hidden within the danger.

These four trigrams are clear-cut; when one casts one of these four, the question is answered.

The next four symbols are a bit more complicated. How they’re read will depend more on the specifics of the situation. Let’s take a look.

Zhen, thunder. one yang line beneath two yin lines. Zhen is sudden, shocking and marks a new beginning (or return). This sign is dynamic but unstable and potentially violent. Zhen suggests a need to wake up or prepare for intensity; it can also suggest that a breakthrough is imminent. Depending on the context this can be read as a dynamic, edgy ‘yes’ with a hint of warning; of this latter group of four, it’s probably the most yes-learning. But it does depend on context and how much intensity is welcome or appropriate. When in doubt, a second cast may be needed to clarify. In any case one should stay alert and awake and watch for volatility.

Xun, wind/wood. one yin line beneath two yang lines. Xun is subtle, gentle, penetrating, mobile and formless—a slippery fish. Xun can signal that the situation is rapidly changing or too unstable to be amenable to a fixed answer (for instance, “will Bitcoin [or substitute a stock or cryptocurrency of your choice] break out of its current trading pattern in the next two weeks?” The situation is too dynamic and unstable to admit of a firm answer). At the same time, Xun can cue us to listen for subtleties and look for signs. What have we been missing? Does the plant realm (wood element) perhaps have a message for us? We may need to get quiet in order to perceive more subtly.

Dui, lake. one yin line above two yang lines. Dui is carefree, open and youthful. It has connotations of pleasure and of barter or exchange. It also symbolizes the mouth. Dui can be read as an easy-going ‘yes’ where appropriate, e.g. in questions of a more lighthearted nature. Otherwise it can point to immaturity, excessive openness, or a lack of clarity (mist/fog rising from the lake). Dui can also be a cue to ask whether the youngest person (or youngest female) present has something to say.

Gen, mountain. One yang line above two yin lines. Gen is solid, stable, closed and conservative. Being fixed in space, it gives a ‘no’ to questions regarding movement or travel, but a ‘yes’ to questions about security and safety. In questions that fall into neither of these categories, it can suggest a need for boundaries, firmness and resolve—or a need to address stuckness or stagnation (Gen’s shadow side). It can also mean “be still, be patient, meditate on it.” This guidance should be followed before casting a second time to resolve any remaining ambiguity.

Divination Procedure

Take a moment to tune in and get grounded. Make a gesture of acknowledgement or thanks to the wider web of forces involved in this moment, perhaps a simple offering (water, a candle, incense, flowers, a song, etc.) to the ancestors or spirits of place if appropriate.

Frame the question carefully. It’s important that the most dynamically positive possible response corresponds to a ‘yes.’ For example, if inquiring about a possible trip, you want to ask “should I go?” rather than “should I stay home?” Failure to observe this principle will lead to confusion.

Take three distinct coins, e.g. a penny, a nickel and a dime. (You can obtain or prepare special coins for use in divination, but it’s not necessary.) When ready, cast them onto your working surface. The penny corresponds to the bottom line of the trigram, the nickel to the middle line, and the dime to the top line. Heads gives a yang line, tails a yin line.

Draw the trigram based on the results. You might scratch it into the earth with a stick.

Interpret as per the principles outlined in the previous section.

Dealing with stubbornly ambiguous trigrams

If an ambiguous trigram’s meaning cannot be intuited upon reflection, you may cast a second time. If the second cast yields an unambiguous trigram, go with this new response. If the second cast yields the same ambiguous trigram as the first cast, accept that the answer is indeterminate; don’t cast again until you’ve meditated on the themes of that trigram. If the second cast reveals a different ambiguous trigram, accept that the answer is indeterminate and consider what factors might be contributing to confusion. Don’t contribute to it by continuing to cast, at least not until you’ve come up with a new angle.

Example Reading #1 - Lost Phone

The other day I misplaced my phone. Logic (and the “find my phone” app) said it must be in the house, but I couldn’t find it anywhere. Finally I thought to cast in order to ask whether the phone was indeed in the house.

Response: yang, yin, yin. Zhen, thunder.

This signaled, first of all, the frustration and anger I was feeling. It also suggested that a return was imminent: the phone would be found, since Zhen is about things coming back around. After the reading, I looked carefully on the East side of the house (since Zhen belongs to the Eastern direction). I didn’t find it there, but did eventually find it camouflaged, green phone on a green tea box. Green also belongs to Zhen.

Example Reading #2 - Structuring Session Work

I asked, “is the time ripe to open up my schedule for Wayfinding sessions?” All three coins came up heads: yang, yang yang. This gives Qian, heaven. A resounding, unequivocal yes. Simple enough.

I then asked, “should I offer one-off Jyotish readings alongside the Wayfinding work?” This was an attempt to address some confusion around how to structure my offerings. This time I got Xun, wind/wood. A less clear response. I spent a few moments feeling into the subtle contours of the situation. Then I realized that, rather than ask again, I could reframe things as follows.

I asked instead, “Is it good to put all my mantic arts offerings under the Wayfinding umbrella?” The response was Li, fire. A ‘yes’ with valences of connection and harmony.

This simple series of questions and answers helped me clarify and simplify an issue that had been nagging me for some time.

Tips

The way to get comfortable with something like this is to use regularly. Play with it. Get to know the trigrams. Give it a try, don’t be shy!

Start by asking questions that have some juice for you but that aren’t completely life-altering in their implications. Go for the medium-sized stuff, in other words.

Keep a journal of your divination results and how things played out.

If you run into trouble, reach out, as this particular version of trigram divination is still in beta-testing. Maybe together we can work out some of the kinks.

Don’t overuse this or any other divination technique, or it will stop working for you.

Respect the oracle—even a mini one like this—as a medium, a tool and a catalyst. It’s not a party trick or a crutch.

Final Note

If there’s sufficient interest, I’d be happy to organize a Zoom workshop or class series on trigram divination. Just drop me a line (jedwardian@gmail.com) or comment below.

Happy divining!

Not that it can’t also extend across oceans. In Cuba they have long substituted coconut for kola nuts and kept a version of the obi practice alive over the centuries.

For instance, suppose you’re on the witness stand and a prosecutor asks “did you eat lunch before murdering Ms. O’Neill?” Assuming you’re innocent, you’re going to need an answer besides ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to do justice to the situation. In other words, binaries can be a trap. This is why even that venerable oracle, the Magic Eight Ball, has a “Try again later” response built-in.

Excellent essay on divination, Jon! Has me thinking. I also believe, like Jodorowsky, that poetry is a trigger, a dream-like message to the unconscious, in the deepest of worlds a continuation divination.

My grandmother had a divination method (casting the bones) but she had another method too. She would go down to the creek with a bag of buckeyes to a large pockmarked stone and ask her subject to place the nuts on the stone until she felt finished, and then she would read the pattern. She said to me "these rocks were made by the old gods of the Cherokee". If you visit Judaculla you'll see exactly what she meant. Thanks.