I’m not generally one to wade into the mire of electoral politics, even so far as to write about the mess. But when the popular discourse starts to bandy around certain terms, I tell coach to put me in. They’re not gonna start talking about who’s weird and who’s not without me weighin’ in!

If you’ve been living under more of a rock than I have, Democrats have lately taken to calling Republicans ‘weird',’ as in “they’re weird” and “say it with me: weird.”

For an incisive analysis of the whole kerfuffle, check out this piece by Ian Leslie of The Ruffian, in which Leslie concludes (agreeing, much as he dislikes the fact, with Vivek Ramaswamy) that the tactic of insulting your opponents is dumb and juvenile, no matter what side of the aisle you (or they) are on.

I’d say the ship of dumb juvenilia in US politics sailed quite some time ago. (Sorry, ‘merica.) But I’ve got things to say about this word, “weird.”

Spoiler alert: it wasn’t always an insult, and we might do well do rehabilitate the term. We need more weirdness, not less—but only the right kind.

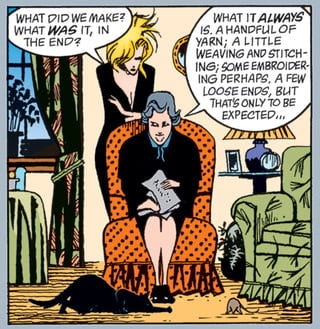

“Weird” comes from Middle/Old English wyrd. As in the wyrd sisters, those three-fold witches found everywhere from Macbeth to ancient Greece, the powers charged with spinning, measuring and finally snipping the threads of our lives. Otherwise known as the Fates.

Those are some weird ladies right there, I grant. Creepy, to the delicate modern sensibility. In truth, their weirdness goes much deeper than a bubbling cauldron or a warty nose. Those threads they’re working are the very threads of wyrd itself. That’s to say, the threads of destiny and fate. The stuff of which our lives are woven, not to put too fine a point on it.

Being wyrd, in the original sense, has to do with being in touch with one’s destiny or inner purpose.

According to an old idea (one I’ve bumped into in diverse places, from Ifa / Orisa tradition to the work of Michael Meade), we all incarnate with a purpose. We may have our debts to pay, scores to settle, pleasures to take, karmas to burn—but deep at the heart of the whole coming-to-earth thing (side note: crazy idea, right?) is the matter of one’s mission, purpose or destiny. This is the crux of the whole biscuit, to use a locution from Frank Zappa (himself at least a mid-level functionary of wyrd).

How do we get from this sense of fatefulness to our sense of weird? Call it a folk etymology if you must, but my theory goes something like this.

In order to have any hope of fulfilling our destiny, whatever it is, we are imbued with particular characteristics and talents. It’s like in Dungeons & Dragons: we only get so many points to distribute among our basic stats. Strength: 14, Intelligence 16? Dexterity only 7 (bam). Or else Dexterity 12, Constitution 17, but Wisdom a lowly 5. No one has it all, or if they do then they probably have a bad case of halitosis to boot. There’s always something to balance the scales.

Take a hypothetical someone whose destiny it is to help develop a Grand Unified Theory of physics. At the risk of reinforcing a stereotype, s/he may not be much use in the hockey rink or on the dance floor. May not be very socially fluent, let us say. Maybe that analytic intelligence score didn’t leave much left over for charisma.

The point is, in the interest of being equipped for what we’re here to do, we’re all wired differently.

You see? wired. weird. All of a piece. Our quirks and foibles are part and parcel of our gifts, or at any rate are inevitable side effects of them. In other words, we’re all weird in one way or another.

And we all have a choice. We can seek to flatten our wrinkles and present a uniform, normal surface to the world. This way we may fit in better, for a little while, among the other normies. Probably not very satisfying. But we may feel safer quashing our quirks.

Eventually, though, if we want to become who we’re capable of becoming, we have to do just the opposite: to embrace our weird and to follow where it leads. It always leads somewhere interesting.

Does this make us weirder? In the eyes of some, sure. But it also leads us to the Others, those whose wyrd matches our own.

Ironically, giving up on trying to fit in helps us to find the place where we actually do fit.

As for a culture that vilifies weirdness, this is almost by definition a juvenile culture. Much like High School, it’s run by the tyranny of the normal (read: dull, non-creative, conformist).

Then as now, we need the weird ones more than ever.

Let me be clear, I emphatically do not mean Trump, his cronies or the masses who have fallen under his spell. There may well be some weirdness there, but it’s not the good kind.

Here we can invoke the late Kurt Vonnegut, who has incidentally provided us with a wonderfully weird schema for categorizing weirdness.

In his Hugo-nominated 1963 novel Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut introduces the fictional religion of Bokononism. One of this cult’s central ideas is the karass.

Stay with me here through a touch of jargon, this is gold.

A karass is a natural grouping of resonant souls, a true cohort whose destiny it is to provide mutual aid and upliftment. A karass can be as small as two people (typically a married couple who work hand-in-glove on some major undertaking: think Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera) or much larger.

History is filled with examples of Karasses. And karasses are filled with people following their weird and finding that it doesn’t isolate them, but brings them together.

On the other hand, Vonnegut presents us with the granfalloon. A granfalloon is a kind of false karass. The author points to identities like ‘Hoosiers’ and indeed, political parties as prime examples of granfalloons.

Karassess are where the good weird flourishes. Granfalloons are normative. No weirdness is encouraged there beyond a narrow set of identifying markers (what’s “on brand”). Granfalloon weirdness is superficial, artificial.

(Since distinguishing types of weirdness is useful, let’s re-adopt the old spelling, wyrd, to signify the desirable kind.)

It’s clear that Trump’s ensorceled followers are mired in a tremendous granfalloon based in fantasy, distortion and bigotry. If there’s weirdness there, it’s not the real stuff, the generative stuff, but only a pallid imitation. Trump has created a kind of perverse safe space for crackpots of a certain ilk, provided they dribble his brand of tea.

As for Harris and co, they’re not wyrd enough.

Despite the re-brand and the new face, the current administration remains committed to the status quo: the promotion of the economic and military interests of the bloated American empire at all costs, and the expansion of corporate profits under the banner of “democracy.” This is no surprise; it’s what the government of such an empire does. You can’t expect the head of the beast to devour the body. But let’s not pretend there’s something inspiring, hopeful or radical going on here.

Even in this business-as-usual context, it’s worrisome to see the would-be left weird-shaming. As Ian Leslie puts it in that same The Ruffian piece,

Using “weird” as an insult ought to be anathema to Democrats. If they want to be the party that stands for freedom, then they should celebrate everyone’s freedom to be as weird as they want. After all, who are the people who most often get dismissed and bullied for being “weird”? We could start with gay kids, Muslims, and go from there. The Democrats are meant to celebrate unconventional sexualities, minority religions, neurological types. They cannot be anti-weird. They have to be the party that says “weird” is good.

Granted, it’s rare indeed to find true wyrdness in politics. Being wyrd means showing your strength and your weakness both; it makes you stand out. Makes you vulnerable. In order to pull that off takes not only being in touch with your inner genius (a high expression of being wyrd) but also the courage and magnanimity to put that on public display.

Václav Havel, avante garde dissident playwright turned Czech president at the fall of the Iron Curtain, had his finger on the pulse of wyrd for a time. Bernie Sanders stands out as a contemporary example, defiantly himself, committed to his ideals and unapologetically quirky.

The wyrd ones are out there. But by and large, at least at the national level, the political landscape resembles a high school cafeteria filled with cliques, side-eyes and backstabbing. In this environment, genuine wyrdness doesn’t stand a chance at winning the popularity contest of an election. Apparently things on the home front haven’t gotten bad enough yet for people to take that kind of risk.

But the thing about wyrd is it never really goes away. It may go dormant, undercover, but it lies coiled under the surface, waiting for its moment to re-emerge and do what it can’t help but do: thicken the plot.